The Science of War

The Science of War

When most people think about war, they picture the tactical level. They imagine squads moving through streets—soldiers clearing rooms. Fire teams bounding. Vehicles peeling off a line of departure. It is natural: that is the level that is visible, filmed, and easiest to understand.

But the deeper reality is that warfare is not won at that scale. Individual tactical actions matter, of course. But once you zoom out, the factors that actually determine victory shift. The world becomes more abstract. The "game" becomes more like competitive decision-making than individual technique. You leave the realm of "how to stack up on a doorway" and enter the realm of "how to shape the entire conflict so the enemy runs out of choices."

If you have ever picked up books like Clausewitz's "On War," you will see a lot of confusing terms. You will most likely be disappointed that he shows no drawings of tactics, battle drills, or the like at any point. But this is indeed the magic of a book that comes from a time and age when the horse was a relevant asset on the battlefield, and still is in a day and age of tanks and drones.

This article is about that jump. Higher warfighting theory. The attempt to understand the more profound logic of war, not just the drills.

Why higher-level theory matters

Combat operations are so complex, with many interlocking factors such as terrain, morale, enemy, luck, and boldness, that we just can't set up formulas to predict the outcome of a battle. Therefore, military game theory is largely abstract. All that can be done is to isolate and analyze the core principles from past battles. Warfighting theory is, therefore, a soft science and of the realm of effects.

What effect do you want to impose? Where do you want to impose it? What is the fastest path to creating that effect? What assumption about the enemy are you exploiting?

This is why higher war theory feels closer to game theory than to range tables. At the strategic and operational levels, you are constantly looking at choices: the enemy's preferences, your own choices, and which decisions constrain the battlefield in your favor.

Clausewitz understood this.

He was criticized for being too abstract — but he was working at the level where drawing a diagram is almost meaningless. The real levers of war are rarely map-clean enough to be diagrammed like a football playbook.

At higher levels, you deal with:

- Friction

- Uncertainty

- Fluidity

- Disorder

- Complexity

- The Human Dimension

- Violence and Danger

- Physical, Moral, and Mental Forces

These elements are real — but they are not systems you can reduce to a simple function. You cannot predict how humans react to novelty, surprise, pain, despair, or sudden opportunity.

War remains, to this day, part science and part art.

So, higher war theory forces us to extract principles rather than formulas. Principles are not precise. But they are reliable guidance — distilled from a long history.

Principles

Mass

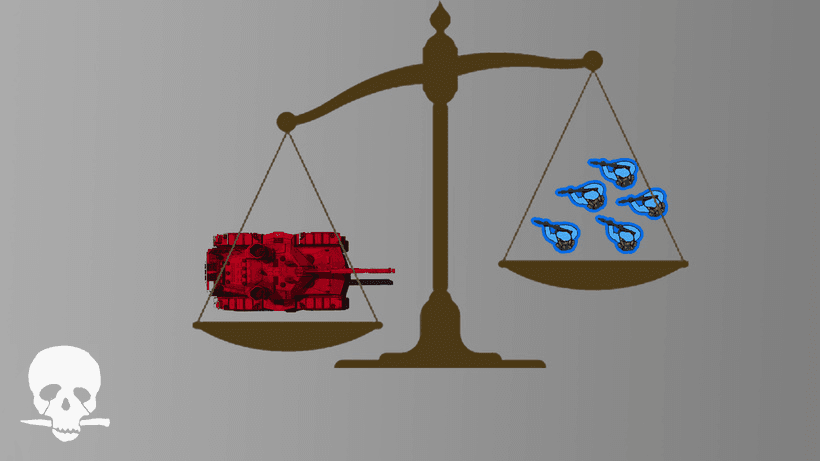

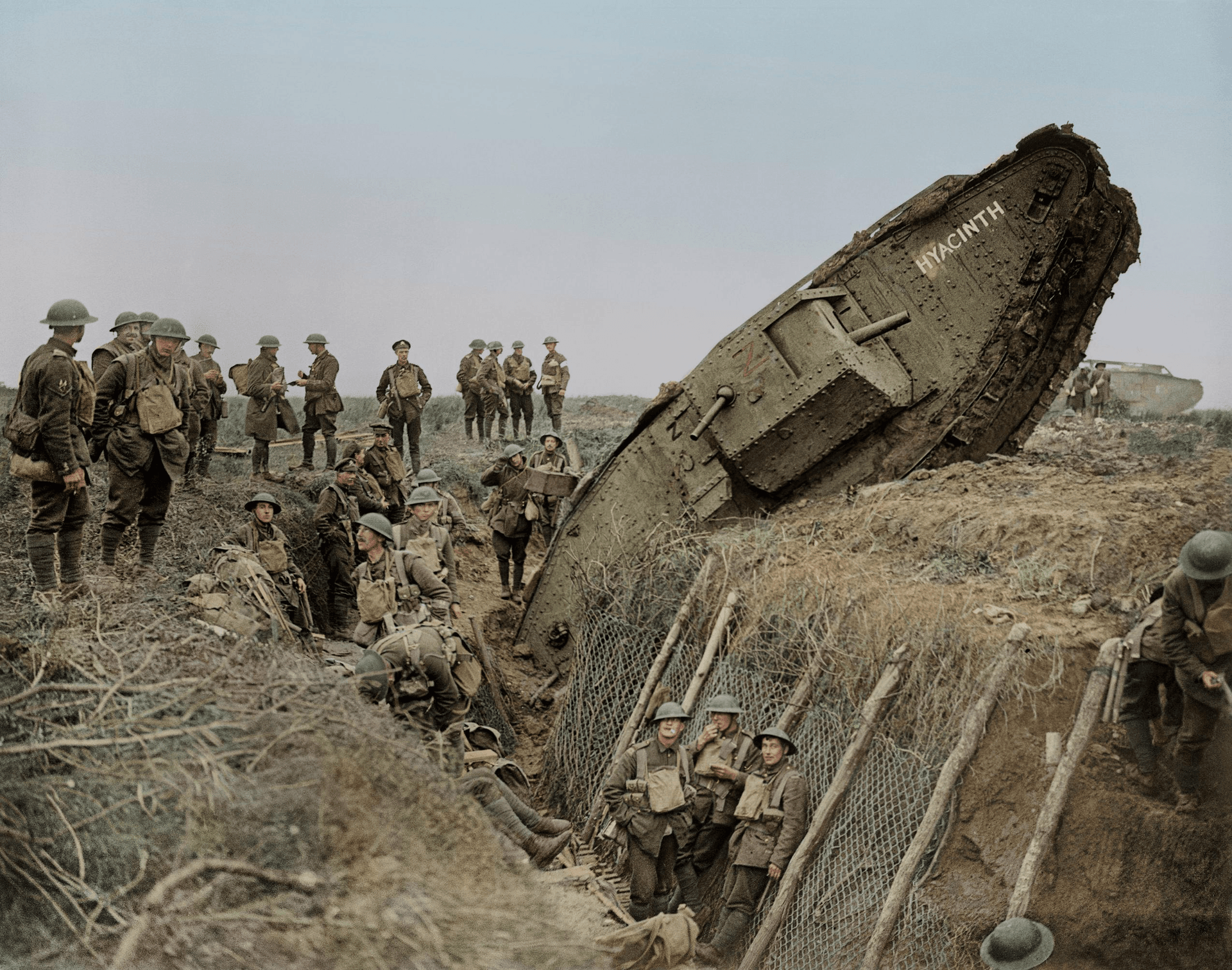

When talking about mass, we are referring to the quantity and quality of a force. Mass is not just sheer manpower; it's the overall "combat value" of a deployed force. Think of mass more along the lines of "weight" than of "numbers". Yes, an infantry squad has the same number of personnel as a tank platoon. But who has the higher impact? Most of the time, it's the tank platoon or even an individual tank.

Generally, mass is considered the most important predictor for warfare. Bringing in a mass that is significantly higher than the opponent's will most likely result in victory in decisive engagements. We should, however, also include factors like quality of training in our calculations of mass.

Density

What density describes is nothing else but the amount of dispersion or force concentration applied. A unit with a high mass that is stretched over a large AO may be inferior to a unit with a lower mass that’s applying force concentration.

Density should however also consider things like overlapping field of fire, terrain considerations can have a major impact on fields of fire. As soon as they are not interlocking or overlapping the element in question will have gaps. Gaps in a layered air defense may for example create weak points.

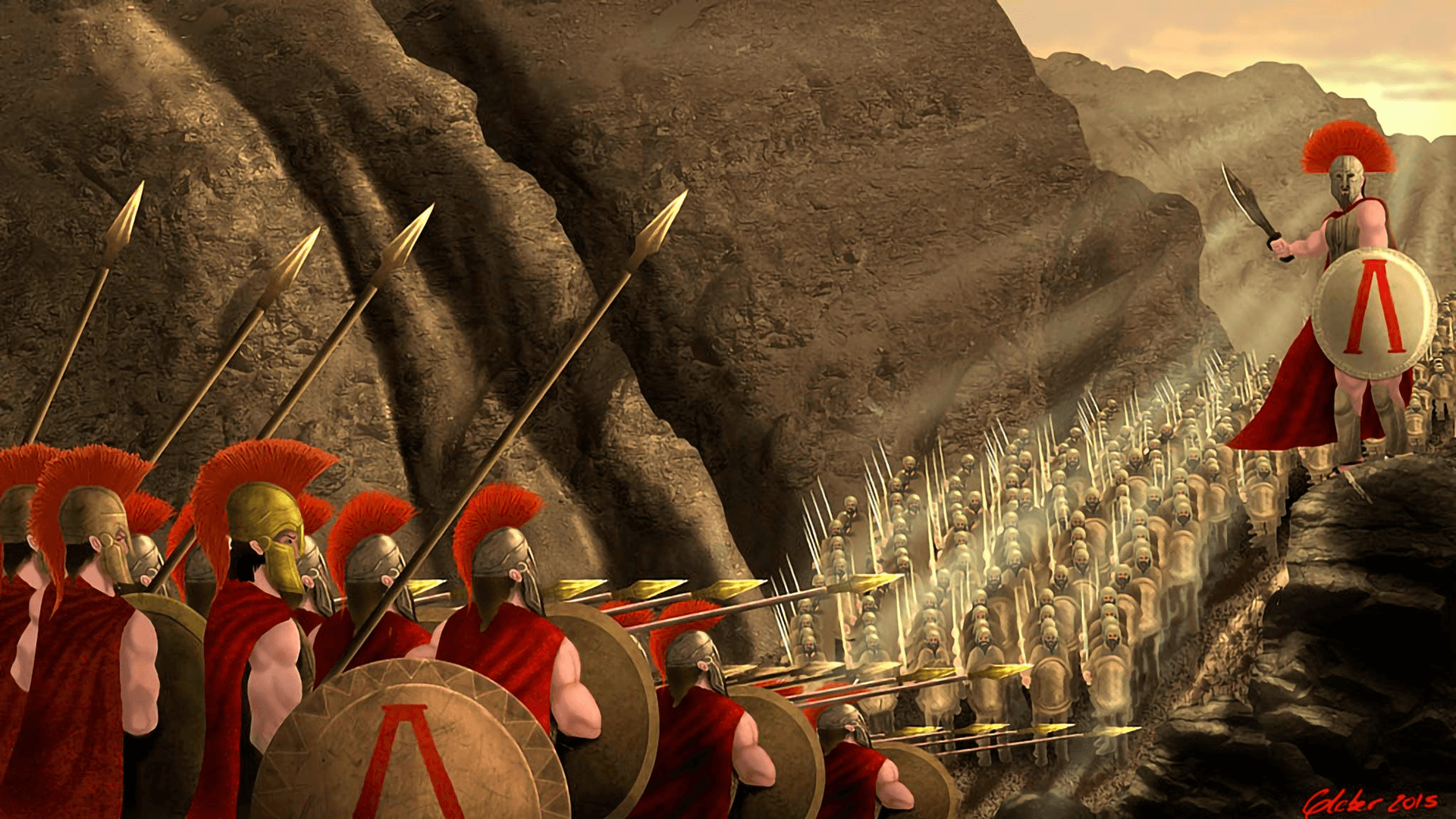

Surface

Surface takes the theory of mass and density to another level. Will the attacking or defending force be able to project a high amount of its mass on the enemy? Terrain and security measures play a huge role here. As soon as terrain channelizes an axis of attack, the attacker cant bring all of his force into direct kinetic engagements. Meaning that a lot of his mass will be idle. Surface also applies to basics such as infantry formations, a column attacked from the front needs to change formation in order to optimize its surface.

A great example for surface is the battle of the Thermopylae where the Spartans faced a force of way higher mass. The result was that the surface of the Xerxes army being so small that it could never be deployed in full mass. Taking the higher training standards and heavier armor of the Spartans into account, the forces of Xerxes that faced direct engagements had to fight an enemy with a higher mass.

Friction

In warfare, things happen that can't be predicted. Bad luck, issues with comms, logistics, and weather, and the like. Clausewitz called this phenomenon friction. Friction should be considered when planning a battle. The longer the battle, the higher the friction; that’s why seeking a quick and decisive engagement with quality troops should always be favored.

B.A. Friedmann had another approach to friction. His idea was that forces would create friction by producing casualties on the other side. A force should always be seeking to create the most friction in the shortest time. This is achieved by combining the factors of mass, density, and surface area most favorably.

Impact

Shooting a machine gun on an infantry squad in an open area is a high impact operation. Shooting the same machine gun at a tank will have little to no impact. Impact describes the efficiency of combat arms in relation to terrain and enemy. Impact is also known as 'Weapon to target match.' All the factors named above can be covered and applied, but they are useless if the chosen weapons have little to no impact. Combined arms and supporting arms warfare aim to maximize the force-to-impact ratio.

Shock and Confusion

Both of these are taking the human aspect of battle into account. A boldly conducted operation using overwhelming firepower, high speed, and violence of action will cause many casualties at a rapid pace and create shock. This shock reaches from the individual trooper being suppressed or literally under shock to the commander who realizes that a small but concentrated maneuver element has penetrated his lines using overwhelming force.

Confusion, on the other hand, is disrupting the enemy commanders' OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) loop. The enemy commander's ability to react relies on several electronic and personnel feedback pathways. Removing command infrastructure, changing angles of attack, and applying deception measures will contribute to shock.

Does this matter to the small unit?

YES! First off, small-unit leaders need to understand overarching war-fighting principles to be efficient in mission command. Furthermore, playing around with those ideas will make you know what you do in an engagement. What happens if I add all my SAWs to my support element? I create greater density with my highest-impact weapon systems! What if my assault element acts fast and boldly? I create shock! Combining all of these principles is how we induce friction, overcome the enemy, and ensure victory!